Church in Russia - 2

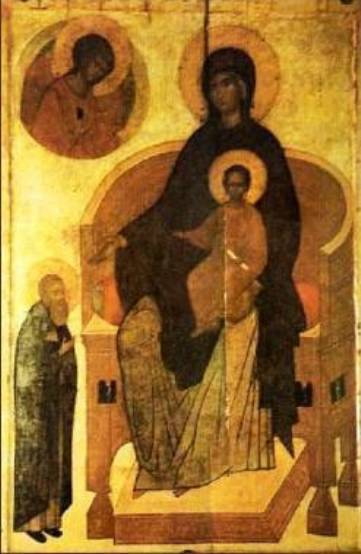

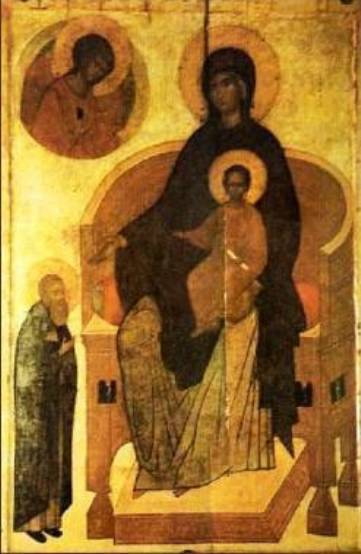

Sergius in front of Theotokos. At the left from above: archangel Michael.

Kulikovsky battle. A medieval miniature.

Map of the Byzantian Empire (about 1400)

Saint Joseph Volotsky

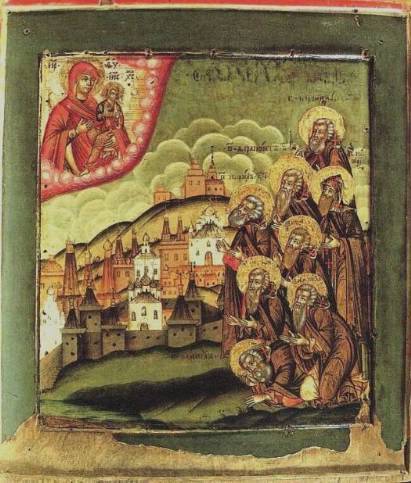

Council of miracle-workers of White Lake, including Nil Sorsky. Icon of the beginning of 18 century.

In the sobornost planted by Sergius of Radonezh the age-old Russian urge to organize life on earth seriously and properly in keeping with the Gospel again manifested itself. In their consistency and full embodiment of spiritual truths in real life the Russian pupils excelled their Byzantine teachers: sobornost in the image of the Holy Trinity became with Sergius the living face of church life which appeared to the whole people as the image of life in Christ.

Embodied in real people united by Christ's love. The image of the Holy Trinity could now also become the object of iconographic representation. This task was carried out by Andrei Rublev in his icon "The Old Testament Trinity" commissioned by Abbot Nikon, Sergius of Radonezh's confrere and successor, in memory and "in praise" of the Venerable Sergius. By embodying Sergius spiritual meditations, Rublev's icon became "theology in painting", a revelation and prophecy about God and man, a new deepening of the traditional doctrine of the Church. At the same time this icon is a real testimony to the fruitfulness of synergism, a testimony to the fullness which the creative human personality can achieve when it does not turn away from God, but grows in the rays of Divine love. No one will condemn us for believing that nothing finer than this icon has been created by the art of any age or nation. Pavel Florensky's statement: "the aesthetic proof of the existence of God":

Embodied in real people united by Christ's love. The image of the Holy Trinity could now also become the object of iconographic representation. This task was carried out by Andrei Rublev in his icon "The Old Testament Trinity" commissioned by Abbot Nikon, Sergius of Radonezh's confrere and successor, in memory and "in praise" of the Venerable Sergius. By embodying Sergius spiritual meditations, Rublev's icon became "theology in painting", a revelation and prophecy about God and man, a new deepening of the traditional doctrine of the Church. At the same time this icon is a real testimony to the fruitfulness of synergism, a testimony to the fullness which the creative human personality can achieve when it does not turn away from God, but grows in the rays of Divine love. No one will condemn us for believing that nothing finer than this icon has been created by the art of any age or nation. Pavel Florensky's statement: "the aesthetic proof of the existence of God":

"Rublev's Trinity exists, so God exists too"

is particularly close to the Russian heart, which from the very beginning was conquered by the beauty of the Word made flesh.

Having begun in the Venerable Sergius monastery, worship of the Holy Trinity spread quickly all over Russia. Many churches of the Holy Trinity appeared, a new church feast dedicated to the Trinity was introduced, second in solemnity only to Easter. Sergius of Radonezh, revered as the "witness of the mysteries of Holy Trinity" became the Russian people's beloved saint. Four centuries after the adoption of Christianity by Prince Vladimir, the Russian Church in the cult of the Holy Trinity showed its people and the whole world the supreme idea of human life, the image of all-conquering beauty, the immortal hope of the future victory of Truth and Love.

The venerable Sergius' teaching on sobornost given visual embodiment in Rublev's icon fell on fertile soil. One might say it became the formative principle of the Russian popular soul, Sergius was surrounded by a whole galaxy of great Russian churchmen, strong individuals possessing remarkable inner freedom and bound together only by like-minded intentions, brotherly love and humility.

But there was nothing in the world stronger and more fruitful than this profound unity of free people. Metropolitan Alexis, the enlightener of the Zyrians Stephen of Perm, Prince Dmitri of the Don, his wife Evdokia, Dionysius of Suzdal, the hagiographer Epiphanius the Wise, the Venerable Cyril of Belozersk, Abbot Nikon of Radonezh, the Venerable Andronicus of Moscow, the icon-painter Andrei Rublev - it is hard to list all the names that belong to this great spiritual brotherhood of Sergius' which encompassed the whole Russian people in its influence. The future of Russia - and not Russia alone - lay in fulfilling the Venerable Sergius behest:

"gazing upon the unity of the Holy Trinity, to conquer the hateful discord of this world".

But the world lies in evil. And when the infernal forces seek to destroy God's world with the insolent and violent self-assertion of crude egoism, then the communal unity bound by meek Evangelical love arises as a dread and invincible host led by the Archangel Michael. In order that we should understand better against whom Sergius of Radonezh was rousing the Russian people, let us quote from Genghis Khan's "Commandments" the following passage describing the moral (or, rather, immoral) foundation on which our age-old enemy based his actions.

"And he said furthermore: man's enjoyment and bliss consists of crushing the rebel, vanquishing the enemy, tearing him out by the root, making their priests howl and turning their wives' bellies into your bed..." V.N. lvanov. My. Harbin. 1926, p. 92.

Is this not what Friedrich Nietzsche was to repeat many centuries later?

"What is good? It's good to be strong... Push the man who is falling... Do not deprive the criminal of the joy of the knife".

What is stronger in the end? What will triumph on earth - the spirit of Sergius or the spirit of Genghis Khan?

The Battle of Kulikovo gave the answer for all time. Its spiritual importance goes far beyond the direct political consequences. If you study the preparations for the battle, its course and how it has remained in the popular memory you will see that it really was a triumph for the spirit of Christian sobornost over the spirit of impious pride. The voluntary uniting of the Russian princes who needed Sergius' exhortations and followed Dmitri was morally far superior to any unity achieved by despotic force. It was a truly free decision of the whole people, born of belief, to resist the evil of the world at all price. And although the Russian princes, beginning with Dmitri himself, did not obey Sergius completely and consequently the fruits of tins great victory were soon taken from them, the Russian people have never forgotten this soborny effort and free resolve of theirs. And at extreme moments in Russian history - in the Time of Troubles and the Second World war, the same resolve has awoken in the depths of the popular soul and the same holy strength has arisen, which won the day on Kulikovo Field.

The historical tragedy of the Tartar-Mongol yoke, the physical victory of the forces of evil, faced the Russian people with the alternative of what to do in the struggle against this evil - to borrow from Genghis Khan the coercive, despotic unity that suppresses the personality or to strengthen the soborny unity which had been preached by the Russian saints. The path of Genghis Khan is much simpler and often more successful, bringing quick and impressive victories.

But victory in the name of what?

What is the point of the struggle itself then, of human life itself?

Only to find how who is the strongest?

But then what difference does it make who wins if the victor is essentially the same as the loser - and the spirit of Genghis Khan triumphs once more? And if the "unity" has been forged by sin and violence, the victor will inevitable lose his strength because of inner stagnation and decline...

During the age of the Venerable Sergius the Orthodox Church in both parts of divided Russia, one subject to the Horde and the other to Lithuania, was a single metropolia of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The strategy of Constantinople, carried on through authoritative churchmen (including the Venerable Sergius) was to unite the whole of Russia to combat Muslim expansion. At that time aggressive Lithuania was still pagan and inclined towards Orthodoxy, the religion on nine-tenths of its subjects. But the willfulness of the Russian and Lithuanian princes, incited by the Horde's cunning diplomacy, prevented this great design from being realized. As a result Lithuania embraced Catholicism and within the framework of the kingdom of Poland lost its former historical role forever.

Russia remained under the overlordship of the Horde for another 150 years. Constantinople was doomed to fall. In a last attempt to save Byzantium, its emperors turned to Christian Europe, but the Pope made assistance conditional upon the Orthodox Church accepting his hierarchical power. In spite of the determined resistance of the monks and lower clergy in the Byzantine Church ("better a Turkish turban than a Papal tiara" they said), the Byzantine bishops under pressure from the Emperor signed the Union of Florence with Rome in 1439. In Russia this was regarded as a betrayal of Orthodoxy. The capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 was seen as Divine retribution for this betrayal (although already in 1443 the Council of Jerusalem abolished and anathematized the Union of Florence).

* * *

It is hard for us now to imagine what a profound shock the fall of Byzantium - not only of the Empire, but also of the Patriarchate - was for the Russian Church and people. The whole picture of the world in that day revolved round this divine center. The situation was further complicated by the fact that Russia had lost this experienced pastoral guidance at a critical moment of apocalyptic expectations.

The year 1492 was 7.000 years "from the creation of the world". The spiritual crisis that took place as a result of this enabled rationalist heretics led by Metropolitan Zosima to take over leadership of the Russian Church. Compiling new Paschal Tables in 1492, he advanced the following argument to "reassure" believers". The prophecies had come to pass and a turning point had been reached in world history. It was the beginning of Christ's kingdom on earth as promised in the Apocalypse (Rev. 20: 6):

"And today in these last years God did glorify Grand Prince Ivan, son of Vasily, the Sovereign and Autocrat of All Russia, the new Emperor Constantine to Constantine's new city, Moscow and the whole Russian Land," -

proclaimed Metropolitan Zosima. This was not simple theological philosophizing. Behind these ideas stood a whole program for the elevation of Moscow. The central act in this program was the coronation in 1498 of Dmitri lvanovich, the grandson of Ivan III, as Tsar. This was something new and unprecedented in Russia! In the Coronation service Dmitri was called "Tsar" several times and received the shoulder mantle and crown of Monomachos, the origin of which goes back to the Roman emperors and even to the kinds of Babylon!

Finally, the state of Muscovy acquired a new coat-of-arms: the Roman-Byzantine double-headed eagle!

The amazing thing is that the authors of the idea of Moscow as the heir to Byzantium, or the "Third Rome", were the heretics around the throne of Ivan III. However, this ideology was soon taken over by the church party of "Josephites" who borrowed a great deal from the Latins. Joseph of Volotsk himself originally shared a completely Catholic position: the limitation of the sovereign's power and his subjection to the authority of the church. In 1497 Joseph broke with Moscow and subjected himself to princes Boris of Volotsk and Andrei of Uglich, who sought protection from King Kasimir. Only in 1507 did Joseph return to the authority of the grand prince, but the main features of his ideology were formed during the lengthy period of the break, when he was under Polish-Catholic influence.

By furiously attacking the errors of Metropolitan Zosima, which for propaganda purposes (but without any justification) he called a "Jewish" heresy (the true origin of this heresy remains unexplained), Joseph was also denouncing the grand prince. In the nature of their criticism Joseph's denunciatory epistles resembled similar denunciations from the Dominican Veniamm, "a Slav by birth and Latin by faith", who translated the Bible under Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod. At this time Joseph wrote:

"If a tsar who rules people is himself ruled by passions and sins, greed and anger, cunning and falsehood, pride and fury, and worst of all blasphemy and lack of faith, that tsar is not the servant of God, but a devil, and not a tsar, but a tormentor... And do you not need such a tsar or prince, who has brought you to dishonor and cunning, for he will either torment you or put you to death".

On returning to Ivan III, who had renounced the heresy (and at the same time broken his oath on the Cross to his grandson Dmitri and made his son Vasily his heir), Joseph changed the nature of his statements on sovereign power radically. He began to stress its "God-givenness" and urge men to serve it "not from fear, but from conscience", etc. Obviously the ecclesiastical secular historians of Russia did not want to accuse the ideology of the Muscovite Autocracy of coming from heretics, and particularly from "Judaisers”. The elder Philotheus was officially recognized as the author of this ideology. A monk from the Pskovian Eleazarov monastery, Philotheus was close to Joseph of Volotsk on the main questions of church government and also, like Joseph, was connected with the Novgorodian Latinizing circle of Gennady and Veniamin. Philotheus' historiosophy was based on Book III of Esdras which Veniamin translated from the Latin version of the Bible (the Vulgate). It was this book (chapters 11-12) that contained the image of the "three-headed eagle" which Philotheus interpreted as the three Romes:

"For two Romes have fallen, but the third stands, and a fourth there will not be".

"Two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and a fourth there will not be" is an arrogant idea of self-sufficiency, the illusion that each "Rome" contains the absolute meaning of its existence in itself, and not in relations with the other two.

This is the principle of individualism transferred to the spiritual-religious sphere. It is not surprising that given such a philosophy spirituality itself becomes confused almost to the point of being identified completely with the elements of stock, blood and nation. "Rome" is now understood not as the Church, not as focal point for a new people, a new mankind, in Christ, but as a center of national might, as a state - and that exists before Christ and outside Christ.

The idea of the Third Rome is a renunciation of original Russian election and a partial renunciation of Christ, of the Russian people's striving to become God's people, to become the Church, to become a soborny organism, to unity in Christ. Holy Russia means the unity of the people in God's name. The Third Rome means the unity of the people in its own name. The flat rejection of soborny relations with other peoples led to a suppression of the soborny element in the Russian people itself.

If we speak of "Rome" not as an empire, but as the Church, then the first Rome continued to stand, in spite of all its sins and weaknesses (and who does not have them!), and the second Rome, the Ecumenical Church of Constantinople, although feeble and humiliated, was preserved by God on earth.

The fact that the Ecumenical Church was left without its state actually made it even more Ecumenical and even more the Church. At a time when the Catholic Church itself became a sovereign state and the Russian church acquired powerful, but also dangerous protection in the form of the state of Muscovy, the Ecumenical Church, persecuted and outwardly helpless, more than any others resembled the early Christian, Apostolic Church. The Church of the Fathers was abandoned by its spiritual children and disciples, but it was not abandoned by God and not released from its fatherly service. In our critical age the decisive word may indeed belong to it...

Two great figures at this turning point of Russian history serve as beacons of spirituality for the following centuries, as a testimony to lost opportunities and at the same time a pledge of future accomplishments: Nilus Sorsky and Maxim the Greek. In their persons Russia rejected the last gift of the Ecumenical Church, until three hundred years later it began its painful quest to return to the roots from which it broke away then. But these three hundred years (which have now become five hundred!) were lost for full-blooded spiritual development. Paissy Velichkovsky, who in the late 18th century began to revive the tradition of synergism, did so not from the heights which Russian spirituality reached during Nilus of Sora's time. Paissy was acting not in the Church of Sergius and Rublev, but in the Church of the Petrine Synod and seminary scholastics...

The great spiritual and theological gifts of late Byzantium - the practice of synergism and the theology of Gregory Palamas - were rejected by the scholastic theologians of the West, and after them by the Latinizing Russian Josephites. Yet it was this doctrine and this practice winch contained the seeds of future Christian culture capable of becoming a field of action for immeasurably more mature human activity which would embrace creatively the whole earthly world. Having greatly weakened the stream of patristic tradition by its rejection of Palamism, Catholic thought was doomed henceforth to merely register, react, sanction, ban and put in order that which it had not created. The creative activity, which had grown up under the protection of the Church but ceased to obtain a living stream of truth and inspiration from it, began to liberate itself increasingly from it. And since creativity is impossible without inspiration, people began to look for sources of inspirations in other places... European culture, with all its brilliance and poverty is the result of this enforced emancipation. Something ever worse happened to Eastern Orthodoxy: while possessing vast potential, it has not realized that potential to this day.

What took place in the Russian Church in the century after the fall of Byzantiuin was a real spiritual catastrophe, the results of which cast a tragic aura over all the following centuries of Russian history. In the final analysis, we arc still reaping remote consequences of this catastrophe even today. The reader not familiar with religious problems may think it strange that such, to his mind, peripheral events as the victory inside the church of this or that trend could have such an all-embracing influence on the life of a whole people.

But for the Christian consciousness, brought up on the Holy Scriptures and church history, it seems quite natural that religious choice should involve a long chain of consequences, determining the fates of individual peoples and, in the final analysis, of all mankind. And indeed here, from the standpoint of faith, we are dealing with the main factor in world history: man's relationship with God. A mistake in solving spiritual questions leads to the violation of this relationship and consequently to all the rest.

These unrealized apocalyptic aspirations confronted Muscovite Russia with a severe spiritual crisis. How should people live now, on what should they rely, where should they direct their efforts first and foremost, in what direction should they build the Church and the State? What lesson should be learnt from the disappointment recently experienced, the meeting with Christ that did not take place? How could they avoid disorder and weakening of faith after such a failure of church judgement the attempt to understand the Divine design or the world, history, Russia and the Church.

The first possibility was to continue to develop and cultivate the exacting truth of the human mind, to deepen spiritual deeds, to develop church creativity; without fearing different points of view, to create a soborny diversity of popular and church life in spiritual rivalry: that was the Hesychast, synergist, Eastern Orthodox path. The second possibility was to stop disorder and vacillation with an iron hand, to ban the discussion of painful and burning issues, to reinforce what had been achieved as eternal canon, to put an end to "uncontrolled" spiritual activity, to place the personal exploit in the strict framework of monastic discipline, to establish a unity of thought and way of life, to unify church ritual, to strengthen the economic and political position of the Church, to make it serve the concrete aims of the growing state.

The spiritual tragedy of Muscovite Russia was not that two diametrically opposed parties arose within the Church - Joseph of Volotsk's and Nilus of Sora's The trouble was that the victory of one of these parties turned out to be too "devastating" because this party remained the only one. Both trends arose logically out of Russian church life, both responded to vital requirements of the day. Joseph's trend responded to the solution of the most urgent and immediate tasks, which is why the majority supported him, But it soon became clear that the enforced rupture of the tradition of synergetic humanism had made the Church in Russia creatively helpless when faced by the great tasks which history was preparing for it. In particular, the higher, ruling strata of society were deprived of spiritual nourishment. Only in the atmosphere of hypocrisy, sanctimoniousness and cruelty established by the Josephites at court could the deformed religiosity of Ivan the Terrible, who resembled the tyrants of the Renaissance (such as Cesare Borgia!), have been formed.

* * *

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Embodied in real people united by Christ's love. The image of the Holy Trinity could now also become the object of iconographic representation. This task was carried out by Andrei Rublev in his icon "The Old Testament Trinity" commissioned by Abbot Nikon, Sergius of Radonezh's confrere and successor, in memory and "in praise" of the Venerable Sergius. By embodying Sergius spiritual meditations, Rublev's icon became "theology in painting", a revelation and prophecy about God and man, a new deepening of the traditional doctrine of the Church. At the same time this icon is a real testimony to the fruitfulness of synergism, a testimony to the fullness which the creative human personality can achieve when it does not turn away from God, but grows in the rays of Divine love. No one will condemn us for believing that nothing finer than this icon has been created by the art of any age or nation. Pavel Florensky's statement: "the aesthetic proof of the existence of God":

Embodied in real people united by Christ's love. The image of the Holy Trinity could now also become the object of iconographic representation. This task was carried out by Andrei Rublev in his icon "The Old Testament Trinity" commissioned by Abbot Nikon, Sergius of Radonezh's confrere and successor, in memory and "in praise" of the Venerable Sergius. By embodying Sergius spiritual meditations, Rublev's icon became "theology in painting", a revelation and prophecy about God and man, a new deepening of the traditional doctrine of the Church. At the same time this icon is a real testimony to the fruitfulness of synergism, a testimony to the fullness which the creative human personality can achieve when it does not turn away from God, but grows in the rays of Divine love. No one will condemn us for believing that nothing finer than this icon has been created by the art of any age or nation. Pavel Florensky's statement: "the aesthetic proof of the existence of God":"Rublev's Trinity exists, so God exists too"

is particularly close to the Russian heart, which from the very beginning was conquered by the beauty of the Word made flesh.

Having begun in the Venerable Sergius monastery, worship of the Holy Trinity spread quickly all over Russia. Many churches of the Holy Trinity appeared, a new church feast dedicated to the Trinity was introduced, second in solemnity only to Easter. Sergius of Radonezh, revered as the "witness of the mysteries of Holy Trinity" became the Russian people's beloved saint. Four centuries after the adoption of Christianity by Prince Vladimir, the Russian Church in the cult of the Holy Trinity showed its people and the whole world the supreme idea of human life, the image of all-conquering beauty, the immortal hope of the future victory of Truth and Love.

The venerable Sergius' teaching on sobornost given visual embodiment in Rublev's icon fell on fertile soil. One might say it became the formative principle of the Russian popular soul, Sergius was surrounded by a whole galaxy of great Russian churchmen, strong individuals possessing remarkable inner freedom and bound together only by like-minded intentions, brotherly love and humility.

But there was nothing in the world stronger and more fruitful than this profound unity of free people. Metropolitan Alexis, the enlightener of the Zyrians Stephen of Perm, Prince Dmitri of the Don, his wife Evdokia, Dionysius of Suzdal, the hagiographer Epiphanius the Wise, the Venerable Cyril of Belozersk, Abbot Nikon of Radonezh, the Venerable Andronicus of Moscow, the icon-painter Andrei Rublev - it is hard to list all the names that belong to this great spiritual brotherhood of Sergius' which encompassed the whole Russian people in its influence. The future of Russia - and not Russia alone - lay in fulfilling the Venerable Sergius behest:

"gazing upon the unity of the Holy Trinity, to conquer the hateful discord of this world".

But the world lies in evil. And when the infernal forces seek to destroy God's world with the insolent and violent self-assertion of crude egoism, then the communal unity bound by meek Evangelical love arises as a dread and invincible host led by the Archangel Michael. In order that we should understand better against whom Sergius of Radonezh was rousing the Russian people, let us quote from Genghis Khan's "Commandments" the following passage describing the moral (or, rather, immoral) foundation on which our age-old enemy based his actions.

"And he said furthermore: man's enjoyment and bliss consists of crushing the rebel, vanquishing the enemy, tearing him out by the root, making their priests howl and turning their wives' bellies into your bed..." V.N. lvanov. My. Harbin. 1926, p. 92.

Is this not what Friedrich Nietzsche was to repeat many centuries later?

"What is good? It's good to be strong... Push the man who is falling... Do not deprive the criminal of the joy of the knife".

What is stronger in the end? What will triumph on earth - the spirit of Sergius or the spirit of Genghis Khan?

The Battle of Kulikovo gave the answer for all time. Its spiritual importance goes far beyond the direct political consequences. If you study the preparations for the battle, its course and how it has remained in the popular memory you will see that it really was a triumph for the spirit of Christian sobornost over the spirit of impious pride. The voluntary uniting of the Russian princes who needed Sergius' exhortations and followed Dmitri was morally far superior to any unity achieved by despotic force. It was a truly free decision of the whole people, born of belief, to resist the evil of the world at all price. And although the Russian princes, beginning with Dmitri himself, did not obey Sergius completely and consequently the fruits of tins great victory were soon taken from them, the Russian people have never forgotten this soborny effort and free resolve of theirs. And at extreme moments in Russian history - in the Time of Troubles and the Second World war, the same resolve has awoken in the depths of the popular soul and the same holy strength has arisen, which won the day on Kulikovo Field.

The historical tragedy of the Tartar-Mongol yoke, the physical victory of the forces of evil, faced the Russian people with the alternative of what to do in the struggle against this evil - to borrow from Genghis Khan the coercive, despotic unity that suppresses the personality or to strengthen the soborny unity which had been preached by the Russian saints. The path of Genghis Khan is much simpler and often more successful, bringing quick and impressive victories.

But victory in the name of what?

What is the point of the struggle itself then, of human life itself?

Only to find how who is the strongest?

But then what difference does it make who wins if the victor is essentially the same as the loser - and the spirit of Genghis Khan triumphs once more? And if the "unity" has been forged by sin and violence, the victor will inevitable lose his strength because of inner stagnation and decline...

During the age of the Venerable Sergius the Orthodox Church in both parts of divided Russia, one subject to the Horde and the other to Lithuania, was a single metropolia of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

The strategy of Constantinople, carried on through authoritative churchmen (including the Venerable Sergius) was to unite the whole of Russia to combat Muslim expansion. At that time aggressive Lithuania was still pagan and inclined towards Orthodoxy, the religion on nine-tenths of its subjects. But the willfulness of the Russian and Lithuanian princes, incited by the Horde's cunning diplomacy, prevented this great design from being realized. As a result Lithuania embraced Catholicism and within the framework of the kingdom of Poland lost its former historical role forever.

Russia remained under the overlordship of the Horde for another 150 years. Constantinople was doomed to fall. In a last attempt to save Byzantium, its emperors turned to Christian Europe, but the Pope made assistance conditional upon the Orthodox Church accepting his hierarchical power. In spite of the determined resistance of the monks and lower clergy in the Byzantine Church ("better a Turkish turban than a Papal tiara" they said), the Byzantine bishops under pressure from the Emperor signed the Union of Florence with Rome in 1439. In Russia this was regarded as a betrayal of Orthodoxy. The capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 was seen as Divine retribution for this betrayal (although already in 1443 the Council of Jerusalem abolished and anathematized the Union of Florence).

* * *

It is hard for us now to imagine what a profound shock the fall of Byzantium - not only of the Empire, but also of the Patriarchate - was for the Russian Church and people. The whole picture of the world in that day revolved round this divine center. The situation was further complicated by the fact that Russia had lost this experienced pastoral guidance at a critical moment of apocalyptic expectations.

The year 1492 was 7.000 years "from the creation of the world". The spiritual crisis that took place as a result of this enabled rationalist heretics led by Metropolitan Zosima to take over leadership of the Russian Church. Compiling new Paschal Tables in 1492, he advanced the following argument to "reassure" believers". The prophecies had come to pass and a turning point had been reached in world history. It was the beginning of Christ's kingdom on earth as promised in the Apocalypse (Rev. 20: 6):

"And today in these last years God did glorify Grand Prince Ivan, son of Vasily, the Sovereign and Autocrat of All Russia, the new Emperor Constantine to Constantine's new city, Moscow and the whole Russian Land," -

proclaimed Metropolitan Zosima. This was not simple theological philosophizing. Behind these ideas stood a whole program for the elevation of Moscow. The central act in this program was the coronation in 1498 of Dmitri lvanovich, the grandson of Ivan III, as Tsar. This was something new and unprecedented in Russia! In the Coronation service Dmitri was called "Tsar" several times and received the shoulder mantle and crown of Monomachos, the origin of which goes back to the Roman emperors and even to the kinds of Babylon!

Finally, the state of Muscovy acquired a new coat-of-arms: the Roman-Byzantine double-headed eagle!

The amazing thing is that the authors of the idea of Moscow as the heir to Byzantium, or the "Third Rome", were the heretics around the throne of Ivan III. However, this ideology was soon taken over by the church party of "Josephites" who borrowed a great deal from the Latins. Joseph of Volotsk himself originally shared a completely Catholic position: the limitation of the sovereign's power and his subjection to the authority of the church. In 1497 Joseph broke with Moscow and subjected himself to princes Boris of Volotsk and Andrei of Uglich, who sought protection from King Kasimir. Only in 1507 did Joseph return to the authority of the grand prince, but the main features of his ideology were formed during the lengthy period of the break, when he was under Polish-Catholic influence.

By furiously attacking the errors of Metropolitan Zosima, which for propaganda purposes (but without any justification) he called a "Jewish" heresy (the true origin of this heresy remains unexplained), Joseph was also denouncing the grand prince. In the nature of their criticism Joseph's denunciatory epistles resembled similar denunciations from the Dominican Veniamm, "a Slav by birth and Latin by faith", who translated the Bible under Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod. At this time Joseph wrote:

"If a tsar who rules people is himself ruled by passions and sins, greed and anger, cunning and falsehood, pride and fury, and worst of all blasphemy and lack of faith, that tsar is not the servant of God, but a devil, and not a tsar, but a tormentor... And do you not need such a tsar or prince, who has brought you to dishonor and cunning, for he will either torment you or put you to death".

On returning to Ivan III, who had renounced the heresy (and at the same time broken his oath on the Cross to his grandson Dmitri and made his son Vasily his heir), Joseph changed the nature of his statements on sovereign power radically. He began to stress its "God-givenness" and urge men to serve it "not from fear, but from conscience", etc. Obviously the ecclesiastical secular historians of Russia did not want to accuse the ideology of the Muscovite Autocracy of coming from heretics, and particularly from "Judaisers”. The elder Philotheus was officially recognized as the author of this ideology. A monk from the Pskovian Eleazarov monastery, Philotheus was close to Joseph of Volotsk on the main questions of church government and also, like Joseph, was connected with the Novgorodian Latinizing circle of Gennady and Veniamin. Philotheus' historiosophy was based on Book III of Esdras which Veniamin translated from the Latin version of the Bible (the Vulgate). It was this book (chapters 11-12) that contained the image of the "three-headed eagle" which Philotheus interpreted as the three Romes:

"For two Romes have fallen, but the third stands, and a fourth there will not be".

"Two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and a fourth there will not be" is an arrogant idea of self-sufficiency, the illusion that each "Rome" contains the absolute meaning of its existence in itself, and not in relations with the other two.

This is the principle of individualism transferred to the spiritual-religious sphere. It is not surprising that given such a philosophy spirituality itself becomes confused almost to the point of being identified completely with the elements of stock, blood and nation. "Rome" is now understood not as the Church, not as focal point for a new people, a new mankind, in Christ, but as a center of national might, as a state - and that exists before Christ and outside Christ.

The idea of the Third Rome is a renunciation of original Russian election and a partial renunciation of Christ, of the Russian people's striving to become God's people, to become the Church, to become a soborny organism, to unity in Christ. Holy Russia means the unity of the people in God's name. The Third Rome means the unity of the people in its own name. The flat rejection of soborny relations with other peoples led to a suppression of the soborny element in the Russian people itself.

If we speak of "Rome" not as an empire, but as the Church, then the first Rome continued to stand, in spite of all its sins and weaknesses (and who does not have them!), and the second Rome, the Ecumenical Church of Constantinople, although feeble and humiliated, was preserved by God on earth.

The fact that the Ecumenical Church was left without its state actually made it even more Ecumenical and even more the Church. At a time when the Catholic Church itself became a sovereign state and the Russian church acquired powerful, but also dangerous protection in the form of the state of Muscovy, the Ecumenical Church, persecuted and outwardly helpless, more than any others resembled the early Christian, Apostolic Church. The Church of the Fathers was abandoned by its spiritual children and disciples, but it was not abandoned by God and not released from its fatherly service. In our critical age the decisive word may indeed belong to it...

Two great figures at this turning point of Russian history serve as beacons of spirituality for the following centuries, as a testimony to lost opportunities and at the same time a pledge of future accomplishments: Nilus Sorsky and Maxim the Greek. In their persons Russia rejected the last gift of the Ecumenical Church, until three hundred years later it began its painful quest to return to the roots from which it broke away then. But these three hundred years (which have now become five hundred!) were lost for full-blooded spiritual development. Paissy Velichkovsky, who in the late 18th century began to revive the tradition of synergism, did so not from the heights which Russian spirituality reached during Nilus of Sora's time. Paissy was acting not in the Church of Sergius and Rublev, but in the Church of the Petrine Synod and seminary scholastics...

The great spiritual and theological gifts of late Byzantium - the practice of synergism and the theology of Gregory Palamas - were rejected by the scholastic theologians of the West, and after them by the Latinizing Russian Josephites. Yet it was this doctrine and this practice winch contained the seeds of future Christian culture capable of becoming a field of action for immeasurably more mature human activity which would embrace creatively the whole earthly world. Having greatly weakened the stream of patristic tradition by its rejection of Palamism, Catholic thought was doomed henceforth to merely register, react, sanction, ban and put in order that which it had not created. The creative activity, which had grown up under the protection of the Church but ceased to obtain a living stream of truth and inspiration from it, began to liberate itself increasingly from it. And since creativity is impossible without inspiration, people began to look for sources of inspirations in other places... European culture, with all its brilliance and poverty is the result of this enforced emancipation. Something ever worse happened to Eastern Orthodoxy: while possessing vast potential, it has not realized that potential to this day.

What took place in the Russian Church in the century after the fall of Byzantiuin was a real spiritual catastrophe, the results of which cast a tragic aura over all the following centuries of Russian history. In the final analysis, we arc still reaping remote consequences of this catastrophe even today. The reader not familiar with religious problems may think it strange that such, to his mind, peripheral events as the victory inside the church of this or that trend could have such an all-embracing influence on the life of a whole people.

But for the Christian consciousness, brought up on the Holy Scriptures and church history, it seems quite natural that religious choice should involve a long chain of consequences, determining the fates of individual peoples and, in the final analysis, of all mankind. And indeed here, from the standpoint of faith, we are dealing with the main factor in world history: man's relationship with God. A mistake in solving spiritual questions leads to the violation of this relationship and consequently to all the rest.

These unrealized apocalyptic aspirations confronted Muscovite Russia with a severe spiritual crisis. How should people live now, on what should they rely, where should they direct their efforts first and foremost, in what direction should they build the Church and the State? What lesson should be learnt from the disappointment recently experienced, the meeting with Christ that did not take place? How could they avoid disorder and weakening of faith after such a failure of church judgement the attempt to understand the Divine design or the world, history, Russia and the Church.

The first possibility was to continue to develop and cultivate the exacting truth of the human mind, to deepen spiritual deeds, to develop church creativity; without fearing different points of view, to create a soborny diversity of popular and church life in spiritual rivalry: that was the Hesychast, synergist, Eastern Orthodox path. The second possibility was to stop disorder and vacillation with an iron hand, to ban the discussion of painful and burning issues, to reinforce what had been achieved as eternal canon, to put an end to "uncontrolled" spiritual activity, to place the personal exploit in the strict framework of monastic discipline, to establish a unity of thought and way of life, to unify church ritual, to strengthen the economic and political position of the Church, to make it serve the concrete aims of the growing state.

The spiritual tragedy of Muscovite Russia was not that two diametrically opposed parties arose within the Church - Joseph of Volotsk's and Nilus of Sora's The trouble was that the victory of one of these parties turned out to be too "devastating" because this party remained the only one. Both trends arose logically out of Russian church life, both responded to vital requirements of the day. Joseph's trend responded to the solution of the most urgent and immediate tasks, which is why the majority supported him, But it soon became clear that the enforced rupture of the tradition of synergetic humanism had made the Church in Russia creatively helpless when faced by the great tasks which history was preparing for it. In particular, the higher, ruling strata of society were deprived of spiritual nourishment. Only in the atmosphere of hypocrisy, sanctimoniousness and cruelty established by the Josephites at court could the deformed religiosity of Ivan the Terrible, who resembled the tyrants of the Renaissance (such as Cesare Borgia!), have been formed.

* * *

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------